Dear readers, fellow gamers,

We hope you are all well and safe.

Who does not love a good gangster story? With subtle threats, seedy trafficking, political corruption and open violence? These ingredients, mixed together, are the bread and butter of many more or less historical successful fictions – the Godfather, Scarface, Peaky Blinders, etc.

China also has its fair share of notorious bandits and infamous gangsters. If some are popular loyal and virtuous heroes – like the 108 stars from the Water Margin, a popular novel written by Shī Nài’ān (施耐庵) in the 14th century – others are despicable ruffians and dreaded killers. Despite their best efforts to reflect the glorious examples of past noble thieves and bandits, the Green Gang were definitely brutal thugs.

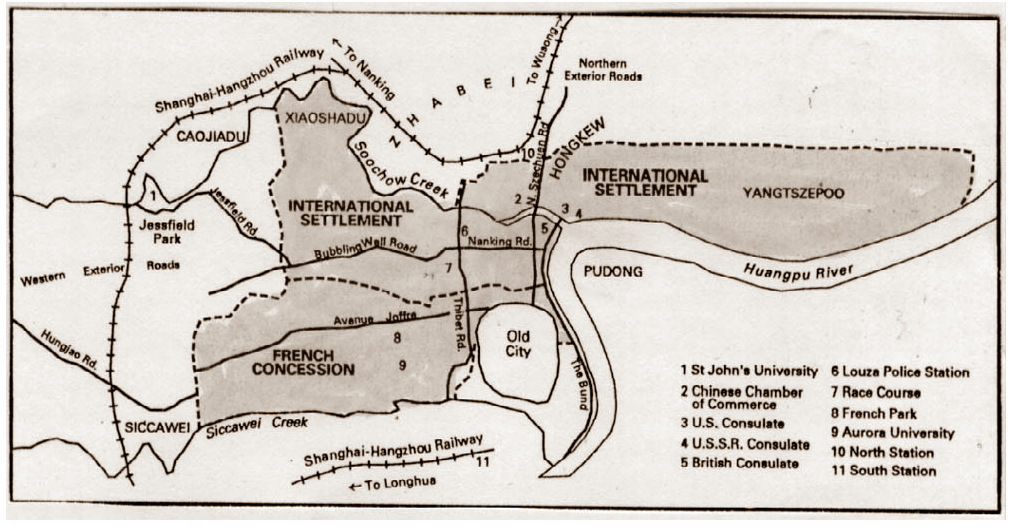

The Green Gang ( 青幫 / 青帮, Qīng Bāng) was a very large organisation, present in many provinces and cities. So large that we will mostly focus on the Shanghai Green Gang, and more particularly, the French Concession Green Gang. Why is that, you may ask? Well, the French Concession Green Gang (Du Yuesheng) will indeed be a playable faction of the Shanghai Uprising scenario. Possessing considerable riches and power thanks to their extensive influence, the Shanghai French Concession Green Gang nonetheless relied on good relations with the foreign settlements and whoever controls Chinese Shanghai to keep their business running.

The Shanghai Green Gang. Politics and Organized Crime, 1919-1937. by Brian G. Martin, (1996) pub. University California Press, Berkeley was super helpful in painting the big picture. A well-written and fairly accessible book to everybody interested in the era and topic, we highlighy recommend it!

And now, without further ado, let’s explore the history, methods and influence of the Shanghai Green Gang with this (hopefully short) series of articles!

Shanghai, a gangster paradise

Shanghai has a long history with secret societies since 1843, the date from which Shanghai became a treaty port. Three reasons made this former unremarkable fishermen’s village into a gangster paradise:

- Shanghai gradually became a key trade port handling enormous volumes of goods traded by sea. The city eventually became the door for opium importations, generating immense sums of money,

- A massive peasant migration from poorer hinterland region in the industrial region Shanghai had become, especially after 1895. Between 1910 and 1930, the Shanghai population tripled from 1 million inhabitants to 3 million,

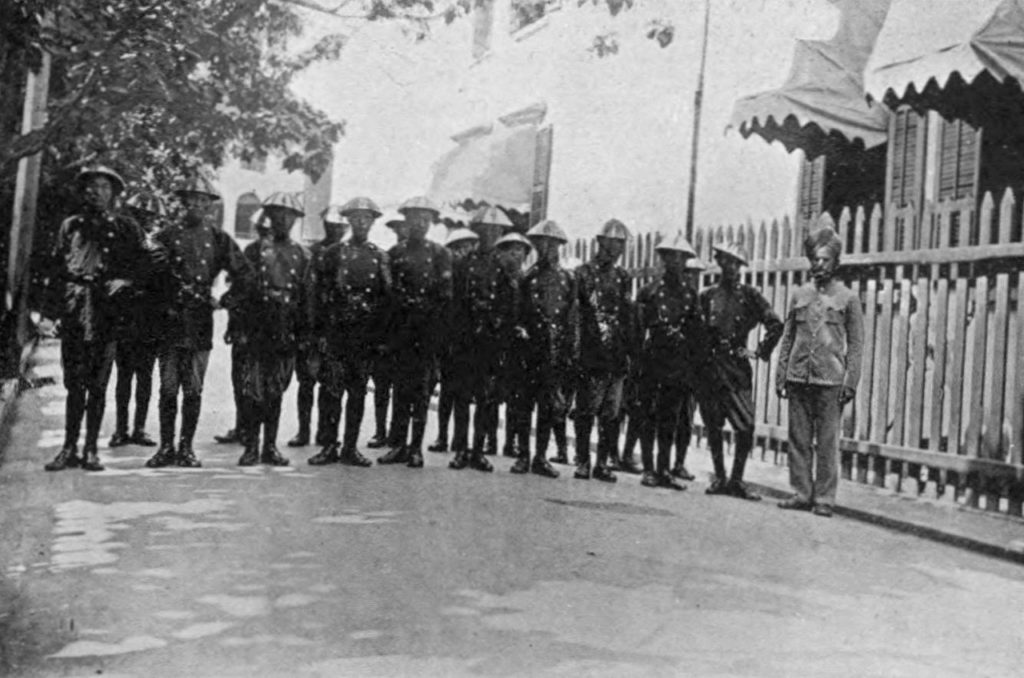

- The presence of three distinct, mutually exclusive police and justice jurisdictions in the cities (Chinese Shanghai, International Settlement, French Concession) made criminal business easier. The three jurisdictions had little to no cooperation between them.

Triads and native place associations

Mostly comprised of men from Guangdong and Fujian, the Triads took roots in Shanghai and quickly grew in influence. Combatted by Qing officials, they were officially proscribed in February 1855. This ban was issued after a revolt of the Small Sword Society which briefly took control of Chinese Shanghai. Secret societies remained alive despite the proscription. The Guangdong-born Shanghainese communities, involved in the opium business, became popularly known as the Chaozhou Clique (潮幫 / 潮帮, Cháo bāng). The Chaozhou Clique was itself part of the Triad groups, commonly designated by the name “Red Gang” (紅幫 / 红帮, Hóng Bāng) from 1900 onward.

Shanghai gangs tended to be organised along native place lines, thought to be a trustworthier, stronger bond between people. The three main providers of Shanghai gangsters were the Ningbo, Shaoxing and Subei areas. Immigrants were recruited in the gangs through the network of native place associations. Native places associations (同郷會/同郷会, Tóngxiāng huì) were organisations born during the Republic era to provide social linkage for newcomers coming from the same area, complementing the more narrowly scoped guildhalls (會館 / 会馆, Huìguǎn). Gangs actively sought to gain control over them to organise racket protection, prostitution, gambling and other illegal activities. Having a foot in these associations also gave gangsters some good control over the labour market, for juicy rackets. Another objective for the mobsters was to impose themselves as « preferred » intermediaries between the Tongxianghuis and others group or public authorities.

Gangsters in numbers

We have been discussing gangsterism for a while now but… can a number be put on these men? Alas, no. There are no reliable figures for the number of gangsters in 1920s and 1930s Shanghai. Scholars nowadays work with an estimation of 100,000 gangsters, i.e. around 3% of the Shanghai population. Most of them were Green Gang members : an early 1930s list of most important Green Gang members reports some 10% of them residing in Shanghai, the largest concentration in China.

A city of crime

Like any large city, Shanghai was plagued with a wide array of crimes, from petty theft to open murder via fraud, smuggling and blackmail. However, two crimes were among the most reported in 1920s and 1930s Shanghai: kidnapping and armed robbery.

Kidnapping

Chinese wealthy capitalists were a prized prey for gangs. Shanghai bourgeois indeed had very high risks of getting kidnapped in exchange for a hefty ransom. This regular issue lead them to hire bodyguards and/or to seek the protection of powerful gangsters, like the Green Gang, to shield them from minor kidnapping gangs. An intense trafficking of children had also developed in Shanghai, notably conducted by the Green Gang. Young boys were sold to rich monasteries or as apprentices in Guangdong and Southeast Asia; young girls would meet a dreadful fate as prostitutes in North China or Chinese coast ports. To give you a glimpse of the extent of this trade: the Shanghai Anti-Kidnapping Society, founded in 1912, had saved 3,782 people (mostly children), between its foundation and 1924.

Armed robbery

Armed robbery was the other major source of threat in Shanghai: between 1919 and 1923, the Shanghai Municipal Police (International Concession) reported 300 arrests of gangsters in charges of armed robbery, frequently associated with murder. This armed robbery issue stemmed from Shanghai being a major smuggling hub for guns, despite the 1919 Arms Embargo Agreement. In 1926-1927, the Chinese customs made some 141 seizures of smuggled arms and ammunitions caches – the mere tip of the iceberg. The wide distributions of guns vastly contributed to make conflicts between gangsters and policemen violent and deadly.

Gangsters as policemen

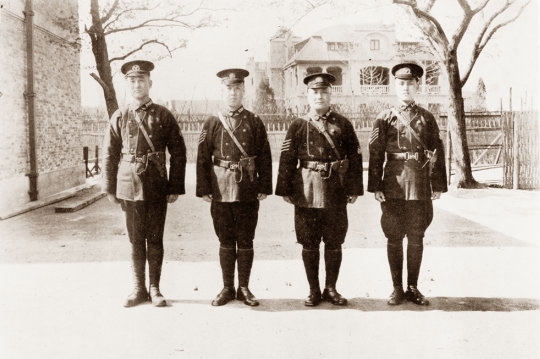

Crime was easy thanks to the existence of three jurisdictions in Shanghai, which were not cooperating with one another. It was made even easier as gangsters infiltrated or were invited in police forces. The most famous examples are Shen Xingshan and Huang Jinrong: the first one, a top leader of the Big Eight Mob gang, was a member of the SMP Chinese Detective Squad; the second, a powerful boss of the French Concession Greeng Gang, was also chief of the Chinese Detective Squad of the French police.

Powerful gangsters also took advantage of the colonial structure of Shanghai to access foreign nominal citizenship and enjoy extraterritorial privileges, notably securing a dismissal of criminal cases in which they were involved. The consuls general of Portugal, Spain and Chile were in the 1920s at the centre of lucrative business of selling citizenship to gangsters. For instance, Du Yuesheng, major figure of the French Concession Green Gang, enjoyed the Portuguese citizenship; Ye Qinghe, “king” of the Chaozhou Clique, had the Chilean one.

Gosh… what a long introduction! We now have (more than) enough background to move on to the actual Green Gang in Shanghai!

The Green Gang: origins, structure and groups in Shanghai

A religious origin

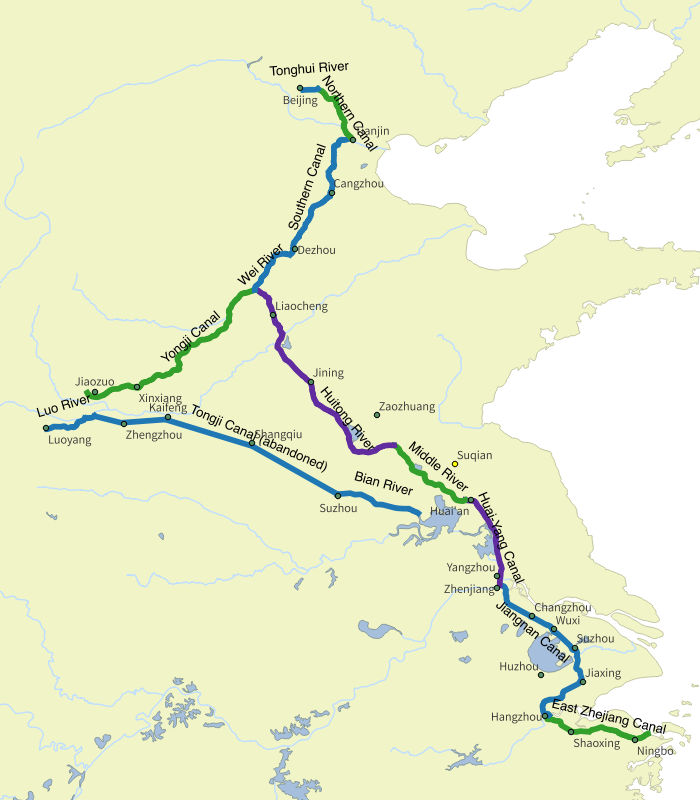

The Green Gang seems to be have its roots in the traditions of the Patriarch Luo Sect. That was a Buddhist sect born during the late Ming era (16th-17th century) and inspired by the White Lotus school. Its founder, Luo Qing, preached individual enlightenment as a paramount value. 18th century Qing official reports date the introduction of the Patriarch Luo Sect among boatmen of the grain tribute fleets. In the early 17th century, these fleets were transporting the grain tribute (漕運 / 漕运, Cáoyùn) on the Grand Canal from Hangzhou to Beijing.

Three men, Weng Yan, Qian Jian and Pan Qing seem to have heralded Patriarch Luo’s believes in south China. They are considered founders of the “Three Patriarchs Sect”, a sub-branch of the Patriarch Luo Sect. This sub-cult became increasingly popular with boatmen’s associations and reached a significant importance in Hangzhou and the Jiangnan area. Having developed a network of monasteries, serving as hostels and temples, the Three Patriarchs Sect was a major player in the areas along the Grand Canal. A player so powerful that emperor Qianlong issued an imperial proscription in 1768 against them. The destruction of the Three Patriarch Sect temples pushed the faith onto the fleet themselves.

Lords of the river

Fleets with their now floating temple were the craddle of the boatmen’s associations attached to their respective fleet. Fleet leaders were selected on the basis of generational seniority. Their influence was so significant that Manchu bannermen protecting the fleets often took orders directly from them. A series of natural and man-made disasters eventually brought the powerful boatmen’s associations to their knees in the mid-1850s.

Some 40,000 to 50,000 men lost their job as the transportation of tribute grain stopped. Some unemployed men joined the Nian and Red Turbans in Subei, Taiping rebels or the Qing armies. Most became salt smugglers in the Liang Huai region of Subei. Salt was indeed a profitable smuggling operation because it was under a state monopoly. High profits could be made by illegally importing it from North China (where it was cheaper) and sell it in the Yangzi concession ports. “Green skins” (青皮, Qīngpí) became the nickname of professional salt smugglers located in the Liang Huai area.

We guess you start to see where the Green Gang name could be coming from…

The disintegrating boatmens’ associations associated with the Pan faction of the Three Patriarchs Sect and salt smugglers eventually allied. From their alliance rose the Anqing League (安清道友, Ānqīng Dàoyǒu) – literally the “Friends of the Way of Tranquility and Purity”. The name may suggest a unified organisation. However, the Anqing League was rather an umbrella for several smaller branches which share a common tradition. Initially smuggling salt in the Subei region, the league to extend its operations to the lower Yangzi area during the 1870s-1880s. Their influence reached a high point around 1890-1900 as the Anqing Daoyou allied with the Elder Brothers Society (哥老會/哥老会, Gēlǎohuì) – one of the most powerful secret societies in China.

Structure of the Green Gang

The Green Gang began to emerge as a distinct organisation from the Anqing Daoyou in 1880-1890, in the Jiangnan area. Scholars have a hard time identifying where the name Green Gang came from.A possible explanation rests in a transcription error of the 青 Qīng (green) character of 青帮 / 青幫 (Qīng Bāng) from 清 Qīng (clear / pure). The salt smugglers’ nickname – “Green skins” (青皮, Qīngpí) – may actually very well be the source of this error.

In 1880, six independent fleets were recreated to revive the grain tribute system and their accompanying boatmen’s associations. Said attempt failed in the late 1880s but gave the Green Gang an organisational framework. It was is organised along lines of fictive kinship in a large family (the 家, Jiā) with three caracteristic features: a « fleet »/gang system, the generational system and the master/disciple relations.

The « fleet » system

The Green Gang kept the « fleet » / gang (幫/帮, Bāng) system from the old boatmen’s associations. This approach made the Green Gang, not unlike the Anqing Daoyou, a loose association of rather independent gangs connected to branches. Six initial branches were dominant in the early 20th century: Jiang Huai Shi, Jia Bai, Xing Wu Shi, Xing Wu Liu, Hang San and Jia Hai Wei. A sub-group of the Green Gang took its traditions from one of the branch, branch which had several groups attached. The various Green Gang subgroups were created between 1885 and 1925. In Shanghai, the two most powerful branches were the Xing Wu Shi, in the French Concession, and the Xing Wu Liu, in the International Settlement.

The generational system

The Green Gang inherited a generational status system from the Three Patriarchs Sect, also used by the Anqing Daoyou. This was initially comprised of 24 generational status groups. First generation members were the ones at the origin of the Three Patriarch Sect; their disciples formed the second generation and so forth. At some point, the Xing generation decided to add another batch of 24. An additional third array of 24 generation status groups were created in 1921.

Members of the Xing, Li and Da generations, like Xu Baoshan (1866-1913), were central in giving birth to the Green Gang between 1900 and 1920. Their followers rose to key positions within the Gang during the Republican era. In the 1920s, four generational statuses were operating: Da (higher seniority), Tong, Wu and Xue (lower seniority).

Being part of a generational group conferred a level of influence and prestige within the Green Gang, but it did not necessarily come with power. Du Yuesheng, from the Wu generation, was powerful enough to give orders to gangsters belonging to the above Tong generation.

Becoming a gangster: entering a master/disciple relation

To become a member of the Green Gang, the applicant had to approach a Green Gang boss, with sufficient generational status. That boss would then, if accepting the request, introduce him to the “teacher” (老師/老师, Lǎoshī or 師傅/ 师傅, Shīfù) the applicant was willing to follow. The application was even taking the form of a written form requiring detailed information on the applicant: family background for three generations, family relatives, native place, age, occupation, etc.

Senior gang members, as “teachers”, were – in theory – the only ones who could recruit “disciples” (徒弟, Túdì, “apprentice”). The “disciples”, when entering the gang, would receive the generational status immediately below their master’s – meaning a Tong master would give his disciple a Wu generational status.

If accepted, the future gang member would be invited to an oath ceremony to formally become a disciple. The whole ritual was heavily inspired by Buddhism, borrowing a terminology from temples. “Entering the monastery” meant applying for membership; “making one’s vows” was the expression used to refer to the customary payment made to the teacher when joining the gang.

If the master / disciple relation was bestowing the generational status is a formal and ritualised way, a more practical form of relationship also existed within the Green Gang. Individuals could choose to take a “master” (先生, Xiānshēng) as their leader, becoming his “pupils” (學生 /学生, Xuéshēng). A pupil could actually have as many masters as he wanted but only one “teacher”. People who were not members of the Green Gang would rely on this type of relations to get acquainted to a patron gangster.

Rules for the men of honour and courage

Green Gang members liked to portray themselves as Háoxiá (豪俠/豪侠, lit. “men of honour and courage”). They sought to appear like the great heroes of the past, fighting injustice on behalf of the poor, the weak and the oppressed. Du Yuesheng in particular was very concerned about his image as a Háoxiá.

All gang members were expected to follow the “ten great rules”, a code of honour. A number of additional rules guiding the members in the gang life complented them. Among these rules could be found the following ones:

- Never deceive your teacher,

- Never disgrace the Green Gang ancestors,

- Respect your seniors with the Green Gang structure,

- Obey the society’s rules,

- Deal fairly with members of the society,

- Keep society’s secrets,

- Avoid adultery and theft,

- Respect Confucian values: benevolence, righteousness, propriety, wisdom and sincerity,

- Assist a member of the society in need.

Guānxì (關係 /关系) and personal relations were central in making somebody rise in the Green Gang. To further cement relations between powerful gangsters, an old Chinese custom was regularly used: sworn brotherhood. Taking the form of rituals with oaths and incense burning, is was quite different from the blood brotherhood as practiced by the Triads. Sworn brotherhood was a good way to help ordinary members build up his personal connections. It also had a use in stabilising alliances between Green Gang bosses. Should a master be somehow outshined by his disciple, a sworn brotherhood was a good way to save face. This was the solution chosen for Huang Jinrong and Du Yuesheng. Oaths were sworn with members of other sects and triads, but also with the larger political and economic world.

The Green Gang in 1920s Shanghai

As already mentioned, the Green Gang – in China as in Shanghai – was not a unified, centrally-led criminal organisation. It was closer to loose structure of independent gangs, sharing traditions and common system. This meant that Green Gang groups were coexisting, cooperating when needed and competing for power otherwise. Among the numerous groups born from the Green Gang, some leaders had their group being significantly influent in Shanghai. In the 1920s, three (or four, depending on the approach) Green Gang centres of influence can identified in the Shanghai underworld:

- Zhang Renkui’s Big Eight Mob in the International Settlement,

- Huang Jinrong’s group in the French Concession,

- Gu Zhuxuan’s faction in Chinese Zhabei plus its Hongkou section in the International Settlement.

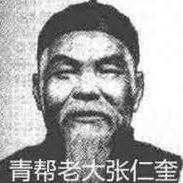

Zhang Renkui’s Big Eight Mob – International Settlement

The Big Eight Mobs were a major player in the early 1920s Shanghai.

The gang was founded by Zhang Renkui (張仁奎 / 张仁奎, Zhāng Rénkuí) (1859-1944) born in 1859 in Teng County, Shandong province. Zhang was the most prestigious Green Gang leader of the beginning of the 1920s in Shanghai. A former lieutenant of Xu Baoshan, well-connected to warlord politics, his influence extended as far Subei, southern Shandong and Jiangnan. Member of the Xing Wu Liu Branch, it is estimated that 40% of all members of the Tong generational status were Zhang Renkui’s followers.

The Big Eight Mob’s influence stemmed from their control over opium trafficking and close links to the Shanghai Municipal Police. Shen Xingshan, one of the gang’s bosses, was a notable member of the SMP Chinese Detective Squad. The gang was however in sharp decline in the mid-1920s, loosing steam against the competing French Concession Green Gang.

Gu Zhuxuan’s group in Zhabei and Hongkou

Another powerful group in Shanghai during the 1920s were Gu Zhuxuan’s men, based in Zhabei (Chinese Shanghai) and Hongkou (International Settlement).

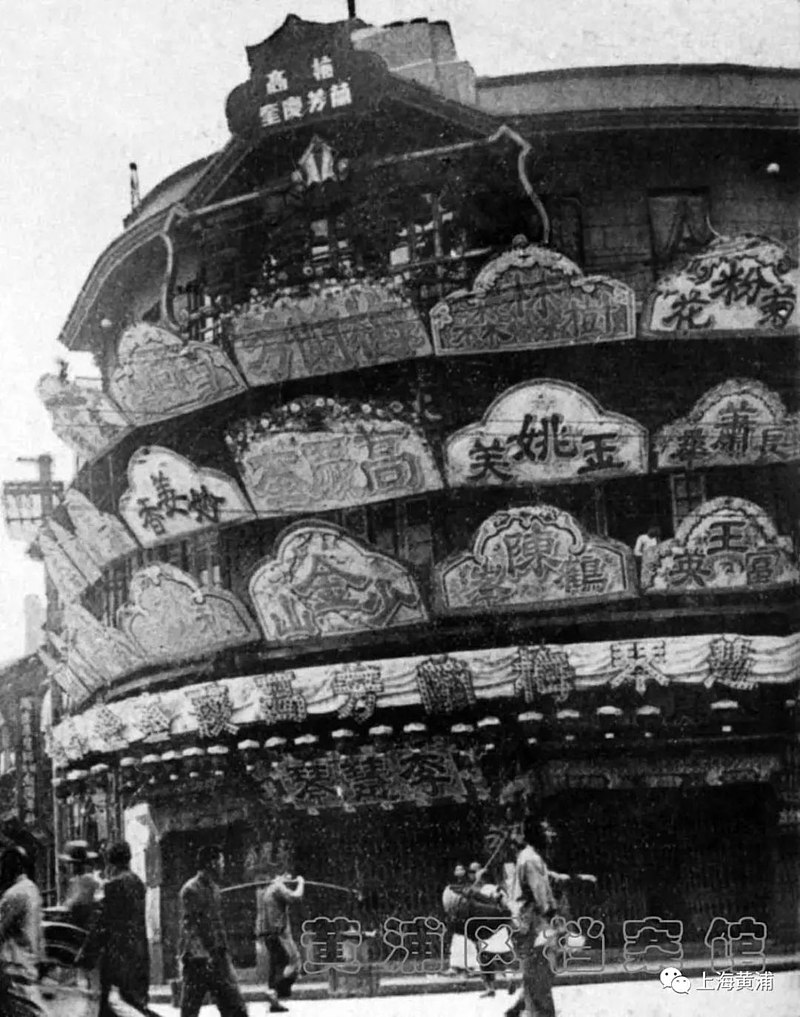

Gu Zhuxuan (顧竹軒 / 顾竹轩, Gùzhúxuān) (1885-1965), born in Yengcheng County, Subei, arrived in Shanghai in 1900 as a rickshaw coolie. After a short service in the SMP from which he was dishonourably discharged, he joined the Green Gang in 1904. Gu got involved in his brother’s rickshaw business and then in the entertainment world in Hongkou-Zhabei. Headquartered in the Moon Theatre (天蟾舞臺 / 天蟾舞台, Tiānchán wǔtái) on Jiujiang Road, Gu was a brutal and cruel person. Described as a “mountain of flesh”, he was known for enjoying detailing the murders he committed to his visitors. Moreover, Gu Zhuxuan became an opium addict in the 1930s.

Gu Zhuxuan’s group took roots in the Subei migrants gathered in Zhabei and Hongkou. Their involvement (and later control) of the Zhabei Volunteer Corps (local militia) and the Jing-Huai Countrymen’s Association was instrumental in their rise to power. The gang had close ties with both uniformed and detective squads of the SMP of Hongkou. As the Japanese influence grew in Hongkou after WW1, Gu Zhuxuan’s group developed good relations with the Japanese there. By the end of the 1920s, his group was estimated to have reached 10,000 followers.

Huang Jinrong’s French Concession Green Gang

Based in the French Concession, this organisation rapidly developed in the 1920s to become the dominant force within the Shanghai Green Gang. A trio of leaders made it the most powerful gang in Shanghai: its founder, Huang Jinrong, Zhang Xiaolin and Du Yuesheng. The latter would eventually become the top dog and gangster king of Shanghai.

Huang Jinrong

Huang Jinrong (黃金榮/ 黄金荣, Huáng Jīnróng) (1868-1953), son of a Suzhou policeman, benefitted from a classical education in Shanghai. Huang was victim of small-pox as a child, leaving him with scars at the origin of his nickname “pockmarked Huang”. Owner of a print-mounting business he launched in 1887, the man spent considerable with gangsters in teahouse. In 1892, he became a detective constable in the French police after successfully seating the exam. Huang began using his policeman influence to build connections with the underworld. He was in bed with the Green Gang long before he eventually formally joined it in 1927.

Being a police officer, Huang was always careful not to get directly involved in illegal businesses. His de-facto wife, Lin Guisheng – ‘Miss Gui’ or Sister Hoodlum – looked after these activities for him. She was particularly famous as the head of the Mahjong Ji Nightsoil Hong company in the French Concession. Some 400 night soil carts were earning her a net profit of CH$10,000-12,000 a month from this activity!

Initially the one true master of the French Concession gang, he was outpowered as the 1920s progressed by his sworn borthers Zhang Xiaolin and Du Yuesheng. His relative decline is dated to 1924 when he was arrested by the Chinese Shanghai garrison for having publicly beaten Shanghai’s warlord Lu Yongxiang’s son, Lu Xiaojia. Zhang Xiaolin and Du Yuesheng intervened and paid to have him freed. This led Huang to resign from his position as chief of the Chinese Detective Squad of the French Police and turn his empire over to Du. Despite the immense loss of face and power, he remained an influential mobster, protected by Du Yuesheng, acting as a balance toward Zhang Xiaolin.

Zhang Xiaolin

Zhang Xiaolin (張嘯林 /张啸林, Zhāng Xiàolín) (1877-1940), born in Cixy Country, Zhejiang, began his working life as machinist in Hangzhou, where he was first acquainted with the underworld. Sometimes in the 1900s, he entered the Zhejiang Military Preparatory School but left without graduating. Working as a ‘runner’ for the Chief Detective of the Hangzhou Prefecture, Zhang earned quite some money by extorting the local peasants. He moved to Shanghai in 1919 to get into gambling and prostitution.

At some point, he became member of the Green Gang of the Tong generational status. Zhang Xiaolin began recruiting followers for his faction and eventually made contact with Huang Jinrong and Du Yuesheng. A tall, distinguished-looking man with a higher degree of literacy, he was to play a central role in the rise if the French Concession Green Gang in the 1920s. Unfortunately for him, the man was also known for his unpredictability, opium addiction and erratic fits of violence; he was even rumoured to have fed an unfaithful mistress to his pet tiger. Zhang Xiaolin resented the influence and legitimacy of Du Yuesheng in the group, nourishing a lasting but contaned feud with him.

Du Yuesheng

Du Yuesheng (杜月笙 , Dù Yuèshēng) (1888-1951) was certainely the most remarkable members of the trio and the one who reached the highest level of power of them all.

Born in a dirt poor family from Gaoqiao District, Pudong County, a real hinterland close to Shanghai, he only had four months of primary education before his family could not afford it anymore. Du remained an illiterate man for most of his life, what made him take a keen interest later in offering free education to poor families through the Zhengshi Middle School he funded. When all his close relatives died, he was placed as an apprentice to his uncle in Gaoqiao but relations quickly degraded between the two, pushing Du into a life spent at the local teahouses and gambling dens. Du would remain passionate about gambling for his entire life.

In 1902, he went to Shanghai to become a bookkeeper apprentice and worked in several shops selling fruits. His time as shop assistant drove him to dabble with local gangsters and introduced him to opium smoking, a habit he would never be cured of despite several attempts. His bad behaviour had him fired from his final work place and he is mentioned for the first time in April 1911 in local newspapers in an article about a drug seller extortion ring. He was later taken under the wing of a brothel madam in Shiliupu where he was in charge of odd jobs for the brothel, including protection of the girls.

After 1910, Du joined the Green Gang through the local gang leader, acquiring the Wu generational status – the gang leader eventually recommended him to Huang Jinrong. This was the starting point of Du’s ascension in the underworld as he began working for Huang’s wife, ‘Miss Gui’, who favoured him. His skills at managing gambling table served him well that he became Huang’s enforcer for gambling and opium activities. Du would from now on often be seen in Shanghai’s nightclubs and sing-song houses or at his four-story house in the French Concession with his many wives and concubines. The successful gangster liked eating luxury food, wearing fine clothes and be accompanied by the most beautiful women under the careful protection of his White Russian bodyguards. He was however quite a supersitious man, carrying three small monkey heads sewn to his clothes.

His rise became unstoppable after Huang’s arrest in 1924, whom he helped out of prison. Huang stepped down and handed over his empire to Du Yuesheng. Now nicknamed the ‘Grand master’ (宗师/宗師, Zōngshī), Du had a large empire of gambling and opium dens, brothels and protection rackets – even controlling two banks and a a large shipping company. With the tacit support of the French authorities, he was at the head of the opium trafficking in the French Concession, earning a fortune. As the Northern Expedition was progressing toward Shanghai in 1926-1927, Du Yuesheng chose to ally the Guomindang to keep his business running. His help was crucial for crushing the Shanghai March 1927 Insurrection.

We will conclude this article here as there is quite a lot of information to process. Hope this gave you a good view of criminality and the Green Gang in Shanghai. The next article on this topic will explore the role of opium for the Frrench Concession Green Grang, their links with the French authorities, their role in the Chinese Civil War and the extent of their power in Shanghai.

Stay tuned for more DDs!