Dear readers, fellow gamers,

We return today with another of our foci, centered this time on the weapons and armament business between Western countries and China during the Warlord era. War was raging during the period depicted in RoWS and China soon became one if not the largest world market for guns! Ready? Go!

Did you know? Chinese warlords would never refer to themselves as « Warlords » (Junfa (軍閥)), which is considered a derogatory term. They preferred to label themselves as « Militarists », « Members of a provincial faction » or « Provincial militarists ». Junfa was however freely used to name the other enemy warlords!

Armament production in China

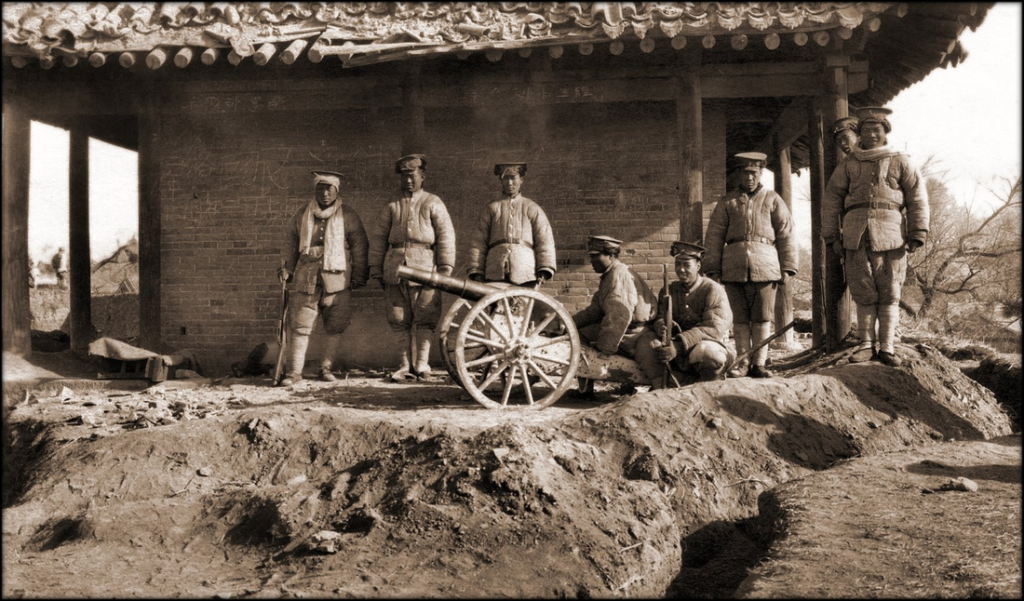

The Chinese armament local production was quite limited and could sustain the old imperial army to a certain extent. When China became fragmented between some 1,300 warlords for more than a decade, this was way below the actual needs.

Only 10 « modern » arsenals had been built in the 19th century under the Qing Dynasty:

- 5 could produce rifles, revolvers and cannons

- 5 were only capable of repairing rifles and hand guns and reloading cartridges.

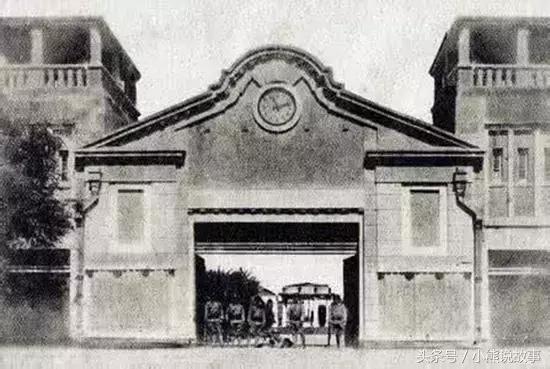

By 1916, this number had grown to 29 arsenals across China, with only 8 capable of producing armament. Some arsenals stand out in terms of size and production like Shenyang, Jiangnan, Taiyuan and Hanyang. The Shenyang arsenal was the most productive one in the 1920s and the only one producing large volumes of ammunation until 1923.

Warlords would attempt to build their own arsenal to ensure, as much as possible, a controlled production of guns and ammunations. Here below you can find an overview of the production of some of them, just to get an idea, around the end of the Warlord era (1928).

A. Shenyang Arsenal (founded by Zhang Zuolin) – 1928 monthly production by 17,000 local workers and 1,500+ foreign workers

- 7,500 rifles

- 70-80 machineguns

- A « large quantity » of artillery pieces

- 9 million cartridges

- 45,000 artillery ammunations (37mm, 105mm & 150mm)

- 120,000 shells cases

- A « large quantity » of mortar ammunations, handgrenades, high-explosive, incendiaries and air bombs.

B. Taiyuan arsenal (founded by Yan Xishan) – 1926 montly production by 800 workers

- 1,500 rifles

- 2.4-3.6 million rifle ammunation

- 500 C96 pistols

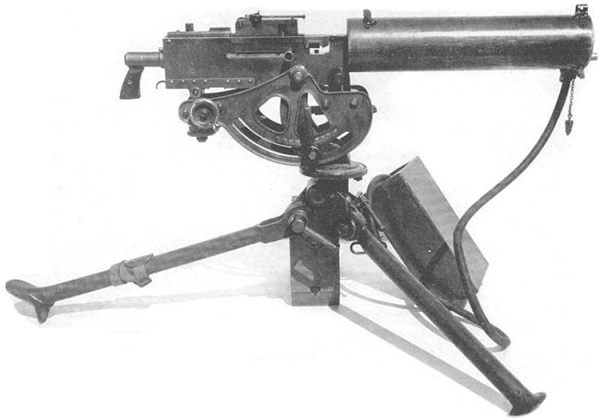

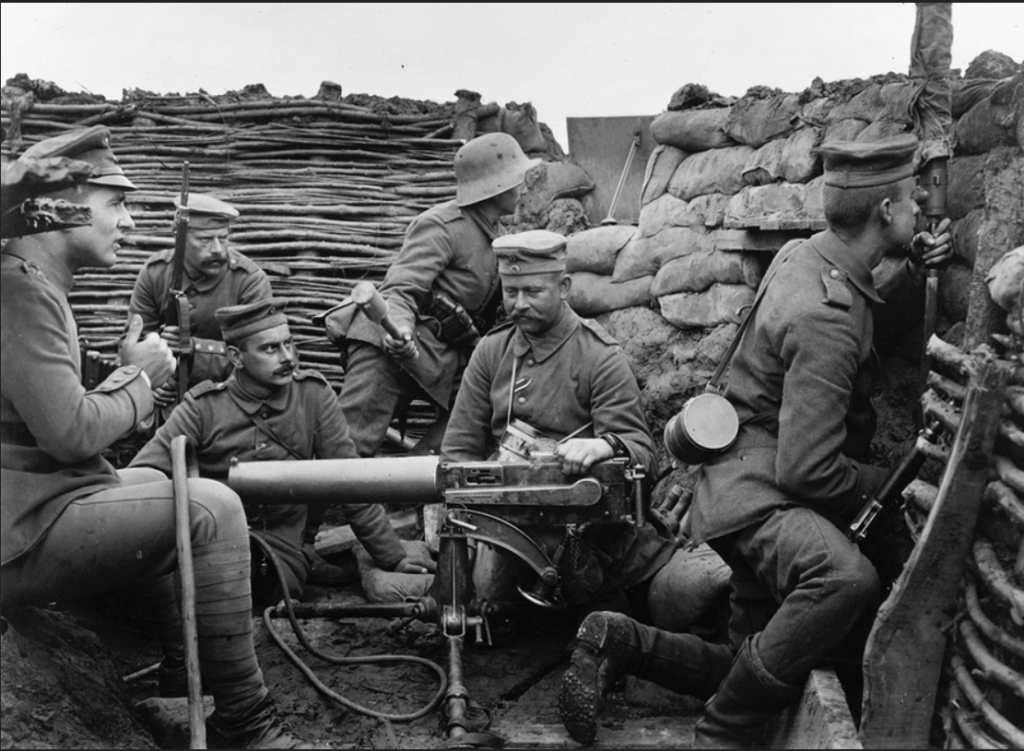

- 30 water-cooled Maxim and Chauchat machineguns

- 300 3-inch mortars

- A large quantity of artillery ammunations and percussion shells

C. Hanyang Arsenal (changed hands several times) – 1928 monthly production by 450 workers

- 6,000 rifles and carabines

- 3,000 Mauser C96 pistols

- 50 water-cooled Browning machineguns

- 3.9 million of small arms ammunations

- 3,000 fuses for 37mm guns

- Aluminium canteens for soldiers

- Stokes mortars, grenades, airbombs

For comparison: D. the Guangdong Arsenal – 1925 monthly production

- 750 rifles

- 700,000 cartridges

- 8 Vickers machineguns

- A number of automatic revolvers

Only one plant was producing aeroplanes in China: the Nanyuan factory, opened in 1910 with a school.

Clearly, the local production, even in 1928, was not sufficient to sustain the warfare needs in China. And which better providers than Western states and Japan to cater for these needs?

Western approaches to the situation

Neutrality and no arms sales to China!

The death of Yuan Shikai on 6 June 1916 led the country to a scission between the North Beiyang government and a rival Constitutional Protection Movement in the South, divided themselves into loosely allied factions which would later split into autonomous warring entities.

A number of foreign powers present in China, lead by the United Kingdom, were in favour of a quick return to peace and business as usual. They sponsored a Peace Conference in Shanghai in February 1919 called by President of the Central Government Xu Shichang. Aide-mémoires were provided by Britain, France, Japan, Italy and the USA. However, strongly opposing views between the North and South led this conference to a failure, with the meeting ending without significant progress in June 1919. Note that fight was still ongoing in Shaanxi and Fujian as the Shanghai Peace Conference was goign on!

Understanding peace would not be achieved quickly, the British were extremely keen on enforcing a neutrality policy from other foreign powers. Among the reasons pushing for such a position, concerns about the Japanese attempts since the early 1910s to carve a political and economic sphere of influence in Chine by supporting Duan Qirui’s Beiyang clique (like sponsoring the creation of the War Participation Army in 1918, to have a Chinese army deployed in Europe for WW1) were major.

Gathering representatives from the United Kingdom, Spain, Portugal, the USA, Russia, Brazil, France and Japan, an Arms Embargo Agreement was agreed, entering into force starting 5 May 1919. Representatives of Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark and Italy were also present and agreed with the text, awaiting official instructions from their respective goverments. The official note from the Dean of the Diplomatic Body informing the Chinese acting Minister of Foreign Affairs can be read here. The text mentioned this was in force until a nationally-recognised government would be in place.

Good words but empty ones

Unsurprisingly, what had been decided with the embargo soon ended up to be empty words. Some tried to keep their words: the British passed King’s regulations to prohibit their nationals from trading arms with China in June 1919. On the one hand, in October 1919, they were approving the sales of Vickers aeroplanes to Duan Qirui (the then « officially-recognised » government). On the other hand, an attempt to buy Handley-Page aeroplanes by Zhang Zuolin and Cao Kun failed twice in November and December 1920 as the British government stood firm on its « no-sales » policy.

The USA also wished to stick to the embargo: in March 1922, President Warren Harding openly supported the embargo and proclaimed that any US citizen caught smuggling weapons into China would be considered a traitor. Funily enough, their representative in the Inter Allied Technical Railway Committee never issued a single objection to the massive transfers of weapons, ammunations and machinery from Vladivostok to warlord Wu Peifu. But, on the other hand, a soldier, Captain Kearney, was caught importing comodities of war from Korea in November 1922, was arrested and judged for treason. Treading the narrow path, hey.

Most were just not playing ball. Remember the Danish delegation present to support the embargo? Well, here is a reply to a British complaint after a Danish company sold machinery aimed at producting ammunations to a warlord:

[There is] no prohibition in Denmark against exporation of these articles and such materials may be shipped freely without the knowledge of the Danish government.

Copy of communication from the Danish Ministry for Foreign Affairs to HMM, 22 May 1922, enclosed in R.C. Parr to Curzon, FO 228/3105, Copenhagen, 24 May 1922

A similar reply would be sent to the Amercians about another deal with a warlord, arguing that the machines sold are not solely meant to produce or repair armament and therefore do not fall under the arms embargo! and this is just a sample of bad faith served to those who dared complaining. You want some more silly excuses? France claimed that the weapons shipments from its manufacturers were meant to equip its policing forces in Chinese concessions – who DESPERATELY needed war aeroplanes for crowd control, you know.

Germany was quite a big provider of weapons to China, especially to Shandong and Anhui warlords. You may argue « How is this even possible for the loser of WW1?! » and you would be right. Germany actually never sold production from its territory to China. Said production was shipped from a third country like, e.g. Netherlands, and therefore not counted as German prohited exports of weapons! Transit countries complacently said to the world’s face that « they do not check cargoes sent from outside the country ». Germany only entered in the arms trade ban on 28 March 1928 after a Reichstag bill where it claimed to be a transit country too.

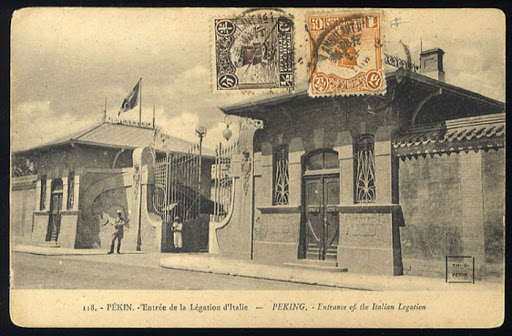

Let us have a look at the most shameless ones in our view: the Italians. The Italian government approved the arms trade embargo on 12 May 1919 but with a special clause: they could sign new contracts with warlords until all great powers approved the agreement! A trick they used to send over 4,000 tons of war materials to China in December 1919 for Shaanxi, Hunan and Manchuria warlords. Catalogues of arms were in open display at their legation in 1921 and their Harbin consul was caught selling arms to bandits! The leftover of their stock was sold in 1924. You want some more? In November 1923, Corporal Bacci struck a $5 million deal with Zhang Zuolin as representative of the Royal Italian Arms Factory to be delivered at Huludao three months later. $500,000 were paid in advance. Three months later, not a single ship with the promised cargo. Zhang Zuolin sent agents to Shanghai to recover the advance payment but was hit by Mixed Court injunction preventing him to do so!

There would be so much more to say but this is already too long!

Forms of armament trade in China

What was traded in terms of arms, equippement, miliary services in 1920s China?

- Well, obviously, guns: rifles, carbines, pistols (those C96 pistols and its derivations were promised to a great future in China), revolvers, machineguns, submachineguns (the Bergman MP28 would become a favourite in China over time). Plus the necessary ammunations, cartridges, maintenance kits etc. Guns and their ammunations formed the bulk

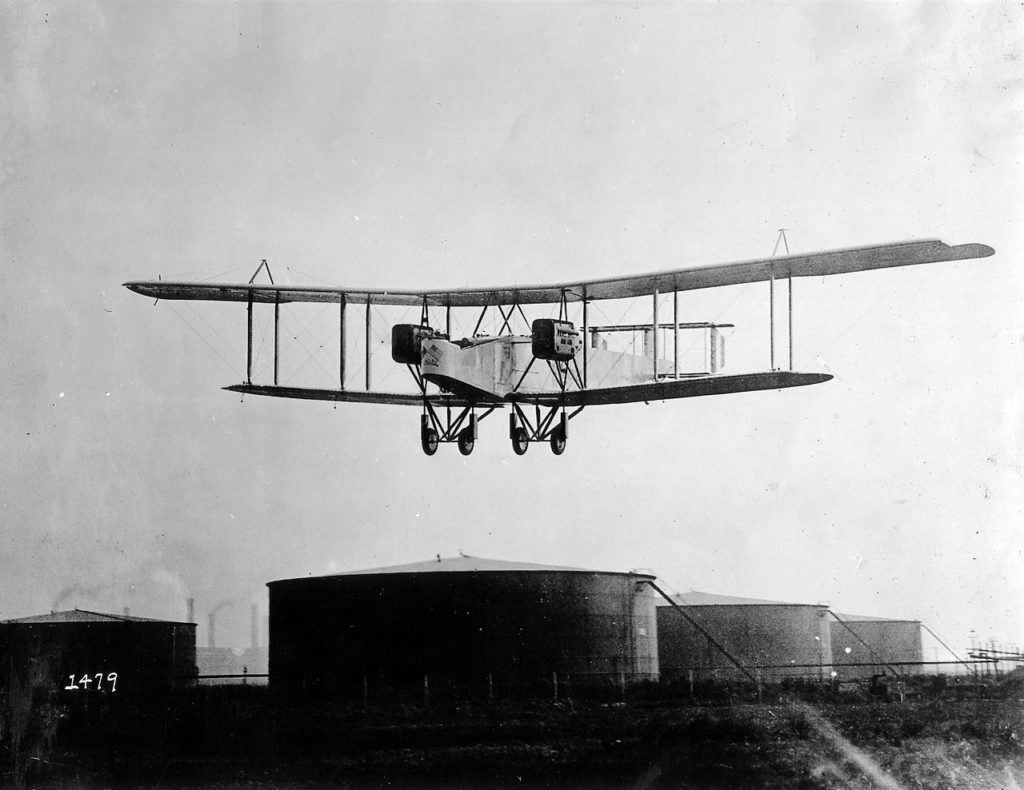

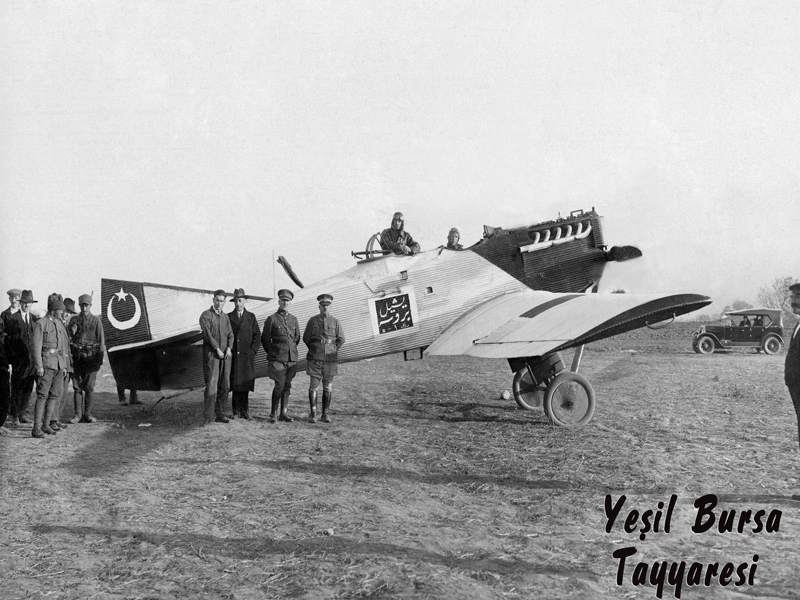

- The Chinese warlords were also quite keen on buying aeroplanes for building up an airforce for reconnaissance and bombing (although at a too high distance). Chlorine gas was dropped by aeroplanes for the first time in China during the Anhui-Zhili war in 1920. The first actual aerial battle took place between the GMD and the Anguojun near Suzhou in December 1927, over a Russian armoured train! Zhang Zuolin assembled the largest airforce of 80 Bréguet and Caudron planes + 60 others to be assembled, followed by the Zhili clique with 88 aeroplanes. Planes would often come with foreign advisors and mechanics to help training the Chinese crews.

Breguet 16

Armstrong Witworth 16 (1930)

Caudron G.3

Vickers Vimy

Junker A35

Avro 540K

- Machinery for producing weapons (conventional, chemicals, etc.) or warfare-related equipement

- Uniform, pouches, leather products to equip men plus all non-fighting equipment (canteen, flasks, shovels, etc.)

- Advisors: foreign advisors were quite numerous in the warlord armies, whether land or aviation experts. Civilian industry advisors were also recruited to set up and run arsenals.

- Mercenaries: China used mercenaries in the 1920s, mostly White Russian forces after the Russian Civil War was lost. They would roam around with their armoured trains and offer services to the highest bidder. Zhang Zuolin was the chief employer of foreign mercenaries, having some 700 Russians as his elite unit – combined with 300 Japanese. Adding 2 Chinese companies on top of this, he named them the Fengtian Foreign Legion which saw quite some action in defending Shanghai against the troops of Sun Chuanfang in October 1924. Zhang Zhongchang (Shandong warlord) also recruited some 5,270 White Russian in his Anguojun forces to fight the GMD in December 1926 together with their 4 armourd trains!

A few names of armament traders of the era

Many companies were involved in this business, either directly or using intermediaries. For era flavour, we though it was nice to list a few – some of them still exist today!

- Anderson, Meyer and Co. (USA) – machines

- Boixo Frères (France) – intermediaries

- Breguet (France) – aeroplanes

- Carlowitz and Co. (Germany) – cartridges and bullet-proof jackets

- Caudron (France) – aeroplanes

- Eddelbuttel and Co. (Germany) – weapons importations in China

- Handley Page (United Kingdom) – aeroplanes

- Jardine, Matheson and Co. (United Kingdom)

- Nielsen and Winther (Denmark) – machine and aeroplanes

- Norsk Spraengstof Industrials (Norway) – explosives

- Nowotny & Co (Czechoslovakia) – arms and ammunations

- State Brno Arms Factory (Czechoslovakia)

- Vickers (United Kingdom) – almost everything you can imagine that is connected to warfare, exported for a total value of £109.3 million to China between 1923 and 1929

Dealing without money?

In 1923, some 60% to 90% of the provincial warlords budget were swallowed by military expenditures. How would they then pay for guns and assistance when they needed more than they could financially afford?

Well, rigths to exploit resources where quite prized. Two examples:

- The Japan-China Forestry, Mining and Industrial Society agreed on 5 February 1922 to a long to Sun Yatsen comprised of ¥5 million in gold, 20,000 rifles, 5 million rounds of ammunation, 72 field gunds, 5,000 shells and 120 machine guns plus ammunation. In return? They were promised development rights on Hainan island and all the other islands of the Guangzhou coast. Plus fishing priviledges from the south of Xiamen to Hainan. Plus first call on forestry and mining rights in Jiangxi. Hell of a deal!

- Tang Jiyao, junfa of Yunnan, gave France exploitation rights over the Gejiu tin mines in exchange for 20,000 rifles, 2 million cartridges and half a ton of explosives plus a French military advisor.

Guiding us in modelling Western arms delivery to warlords and for this article, let us introduce the fantastic book by Chan A. B. (2010), Arming The Chinese: The Western Armaments Trade in Warlord China, 1920-28, Second Edition, Vancouver: UBC Press.

This 216-pages book was a really helpful sum of information, packed with in-depth details on « official » and shadier deals.

Here is a direct link to UBCPress if you are interested in getting the book at a decent price!

And this, fellow gamers, conclude this long Focus. Covering the wide numbers of deals made during the time would have been impossible. We however hope that the overview provided was of interest to you! Stay tuned for more DDs.

À propos de l’auteur