Dear readers, fellow gamers,

We hope you are all well in theses difficult times of Covid-19, stay home and stay safe!

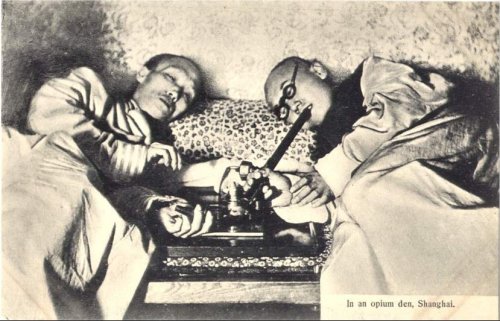

Today’s post is a focus (as the title implied) on opium. We have all have in mind stereotypical images of Chinese people, lying down in cloudy opium dens, opium pipe in hand, looking dazed and spleepy.

These clichés are unfortunately an accurate reflection of what an opium den looked like in the 19th and early 20th century. Opium has poisoned the Chinese society for more than 100 years and been instrumental in putting the country in a torpor which would only be really shaken in the 1920s.

Today, we will take you on a journey through the dark history of opium in the 1920-1930s China!

Opium – brief description

First, there is a need to describe what opium is, how it was then consumed and what its effects are.

Opium (or poppy tears, latin: Lachryma pappaveris) is a latex obtained from the seed capsules of the Papaver somniferum variety. Containing up to 12% of analgesic alkanoid morphin (and other niceties like codein, thebaine, papaverine and noscapine), this latex can either be consumed as opium or chemically processed into morphin – which can in turn be refined into heroin. Morphin, as a painkiller, has medical uses.

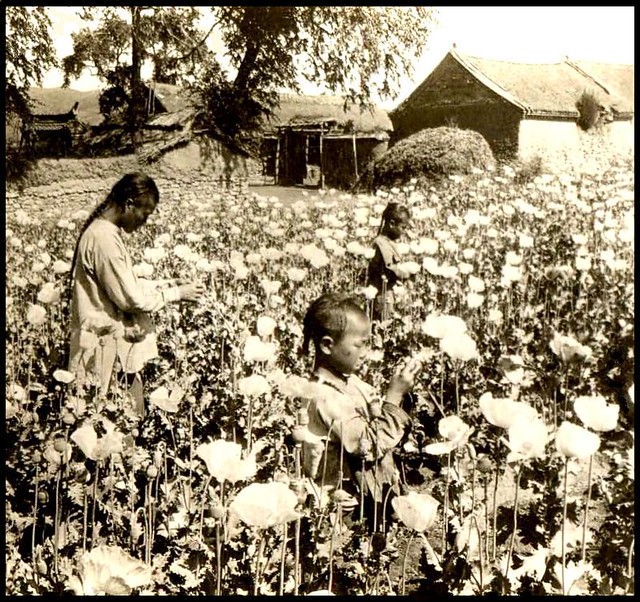

The collection of opium latex is labour-intensive, requiring the collector to manually scratch immature poppy pods. The latex then leaks out and eventually dries to a sticky yellowish residue, which is scratched off and dehydrated.

Opium was smoked at the time. Using long metal pipes with a removable knob-like bowl. A small ball (« pill ») of opium, approximately the size of a pea, would be placed in this bowl-end of the opium pipe and heated at a temperature at which alkaloids vaporise. Lying on his/her side, the smoker would guide the pill around the heat source and inhale the fumes when he/she pleased. Several pills were consumed in one session, depending on tolerance and addiction. Effects would usually last up to 12 hours after smoking.

The consuption of opium induces a sense of orgasmic extasis, intense relaxation, insensibility to pain (due to the morphin), difficulties to coordinate movements, etc. In a nutshell, smokers were put in a dream-like state. These effects are the main reason why opium smokers are consuming it in a relaxed, lying down position. Opium consumption leads the consumer to develop tolerance and strong addiction. Overconsumption has nasty, unpleasant side-effects: constipation, respiratory distress. Regular smokers with no means to sustain their consumption are often emaciated, lean as they have lost appetite. Their eyes are listless and dull. Forms of dementia may appear.

Opium in China, prior to the Qings

The first mention of opium in the Middle Kingdom goes back to the Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD). Opium was then used as medicine for treating diahrrea, malaria and many other ailments. This cure was ingested orally. There was no negative social connotation attached to its consumption. Medical use is the only one which is attested until the 17th century.

The arrival of the Westerners during the final decades of the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) was a turning point in this regard. The Portuguese, Spanish and Dutch sailors introduced American tobacco in China. Smoking and cultivation subsequently spread from southern China to the rest of the empire. Around the same time, the Dutch started mixing tobacco and opium – a habit quickly adopted by the Chinese as well. With all Chinese ports opened by decree in 1685, trade became easy for the Westerners. By the end of the 17th century, yapian (consumption of unalterated opium) had replaced consumption of the opium-tobacco blend across China.

Failed attempts by the Qing to prohibit opium

Qing Emperor Yongzheng decided to issue a opium smoking prohibition edict in 1729. Weirdly, this ban did not target sales and consumption for medicinal purposes. Opium imports still being taxed, law enforcement was unsurprisingly extremely lax. During the following 50 years, opium imports and homegrown cultivation boomed.

The ban was renewed in 1796 and 1799 by Emperor Jiaqing, without any ambiguity left in its text and application, but the harm had been done. Starting in the late 1700s, the British, who were looking for a way to reverse the imbalance of their trade with China, began to smuggle massive amounts of Indian opium. This lucrative trade, involving Westerners (mostly Britons), Chinese merchants, officials and criminals, bleeded the Qing dry of manpower and coins.

The whole Chinese currency system, since the Ming decision in the 1570s to receive all tax payments in silver only, was based on silver coins – mined in America and exchanged for chinaware, silk, tea and other high-value goods. Peasants paid in copper coins but taxes were calculated and sent to Beijing in silver taels. The unfair opium trade led by the British resuled in a sharp appreciation of the silver tael, which forced the Chinese people to pay higher taxes (in copper) for no real increase in revenue for the Imperial court (in silver).

Further edicts in 1800 and 1809 proved useless in stopping the trade.

Ban or legalise? That is the question.

Debate took place in 1836-1838 over legalisation:

- Xu Nanji, president of the Sacrificial Court, defended legalisation in an effort to halt the silver exodus from China – opium would carry a minimal tax and could only be bartered. He also promoted home cultivation, arguing that local varieties of opium were less addictive. Additionally, scholar, officials and soldiers would be prohibited to smoke.

- Huang Juezi was dead-set against opium, advocating death penalty for addicts, cultivators and traffickers.

- Lin Zexu – governor of Hunan and Hubei – also an opponent, wrote in 1839 a memorandum that appealed to the Emperor. He proposed a dual approach. On the one hand, compassion for the addicts, with a one-year grace period to be cured of their habit (with state-sponsored drug treatment facilities) or facing death should they fail to. On the other hand, harsh treatment against both native and foreign traffickers: summary imprisonment and death penalty.

Lin Zexu was appointed Imperial Commission for Frontier Defence and disptached to Guangzhou/Canton where he supervised destruction of imported Indian opium in 1839.

Opium unchained!

Guess who was not pleased with this decision? The British, of course! Coming with soldiers and gunboats, they waged a war to China between 1839 and 1842. They secured an easy victory and imposed a disatrous treaty, seizing Hong Kong, opening 5 treaty ports, securing war compensations (21 millions yuans!) and got to set with Chinese the custom taxes level.

The legality of opium trade was only addressed 10 years later. The 1858 Treaty of Tianjin and the 1860 Convention of Beijing touched the issue: a 30-tael duty was fixed for each picul (roughly 133 pounds, 60,8kg) of imported opium. In 1876 and 1885, two more documents raised the duty to 110 taels. However, duties did not prevent home growth!

In 1905-1906, at its peak, China was producing some 7/8 of the world opium production! This is explained by the fact that the supply from India was severely disrupted after a series of devastating rebellions between the 1850s and 1870s (Taiping, Nian and Muslim). Opium was a true cash crop. It helped rebuilding the economic fabric and was a sort of revenge against those « white devils ». In 1906, a chronic Chinese addict would consume 8 grams of opium a day, so market opportunity was strong!

The social art of opium

Opium smoking was widely viewed as cure for multiple ailments or as a stimulant. Gradually, over the 18th and 19th century, it became a commodity for social relations. Among such social intercourses were visiting prostitutes, gambling or just whiling away the time. You may compare it to coffee, when speaking about occasional consumers.

Smoking was rarely done in solitude, it was a highly social activity. Welcoming a guest with an opium pipe was common gesture. Rich hosts would lavishly welcome the guests with expensive Indian opium while poorer ones would rely on local production, like in Sichuan. Smoking material would of course be provided to the guests. Local elite considered opium smoking as a sign of refinement and status. In Western China, you could even gauge the household’s wealth by the number and variety of opium pipes on display.

Addicts bearing visible sign of their condition were however disregarded as people not capable of controlling themselves and shuned by the Chinese society. Opium is often cited as a key reason for marriage and familial life collapsing. Young girls were often mortgaged to opium dens, becoming « Flowers » and attending the smoking customer.

Moving against opium

Foreign missionnaries began to alert the Qing government in the 1880s. Their voices were much strengthened by Chinese students returning from their studies abroad and Chinese Christians during the next two decades. The Imperial Court eventually responded with a ten-year plan to combat opium addiction in 1906. This plan, estimating that 30-40% of the Chinese population was addicted to opium, entailed addicts registration for detox and progressive reducation of cultivated surface of opium.

Cooperation with foreign power was actively sought, notably with the British. An agreement was found. From 1 January 1908 onward, Great Britain would reduce its Indian opium exports to China by 10% a year, over 10 years. Three years later, a further agreement to stop them all at once was to be signed but the Chinese Revolution got in the way.

Agreements with other foreign powers were secured between 1908 and 1914. Impressive results were achieved at central and regional levels despite the change of regime and the policy remained mostly intact.

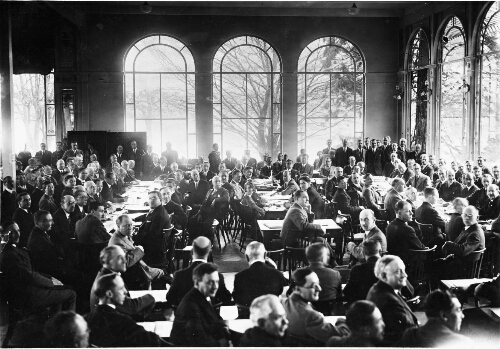

Unfortunately, the central policy could not stop such a beast with a single blow. In 1917-1918, some 80% of the world production was still in China. Opium conferences were convened in Geneva in 1924-1925: the Chinese delegation eventually stormed out when a proposal was put to organise legal state-controlled sales of narcotics in Asia.

As China was further disintegrating into regional fiefdoms, opium flourished. Complicity and interested encouragement by regional warlords proved themselves significant boosts to trade. But this, friends, is another story!

We hope this quite in-detail focus was of interest to you, stay tuned for part 2 (the 1920s-1930s) in the coming weeks!