Dear readers, fellow gamers,

We today initiate the return of our focuses with a key topic for Rise of the White Sun: armies, and more specifically soldiers that comprise them.

What would a warlord be without armed men to do his bidding? Nothing. The whole era would not have existed without the huge number of armed men having a different allegiance than the central Beijing government. And, the game willl

This first article on the topic owes its fantastic deal of information to Diana Lary’s book Warlord Soldiers – Chinese Common Soldiers 1911-1937. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1985. 177 pages. That one is a solid and short (111 pages without appendixes, notes, bibliography and index) academic introduction to the topic. Even better, the read is rather easy and fluide. In a nutshell, well worth the money and time!

And now, without further ado, let us jump into the soldier life in the 1920s!

« You may not need soldiers for a hundred years, but you cannot be one day without them. »

Confucius

Surprising, coming from the man who advocated the supremacy of civilians over the military, isn’t it? Well, the great sage still acknowledged soldiers had a role to play in order to make the state secure and peaceful – to protect it from external aggressions and safeguard internal order. The military was to act as a passive deterrent rather than an active force but they nonetheless remained crucial. Should they fail, chaos would follow. And it did.

From guardian of the Empire to sources of disorder

China was heavily shaken in the 19th century by two things: large revolts and the Western aggressions. The Qing attempts at modernising its forces (Xiang army [1850-1864], Huai army [1862–1894] and the New Armies [1895–1912] came too late and were too limited in scope. By the time the Empire had a somewhat decent military force, the Westerners and Japanese were no longer interested in attacking China for territories. This left Qing soldiers with no external enemy to deter or deal with until 1932 and the Japanese attack on Shanghai. These men were left with the sole preservation of internal order. They soon became the major source of disorder!

The 1911 Xinhai revolution that overthrew the Qing dynasty started from a mutiny of New Army soldiers based in Wuchang (district of nowadays Wuhan, merged with Hankou and Hanyang). The army, as a central element of the Revolution, began growing self-confidence among the soldiers. They were no longer struggling with the powerlessness feeling from their predecessors, who repeteadly failed at resisting foreign encroachment. Increased militarisation went with growth of violence as soldiers’ status was on the rise.When President Yuan Shikai died in 1916, militarises no longer under control. Thus begun the Warlord era, fuelled by huge numbers of soldiers idling in peace time…

Wars in the 1920s

And they jolly did fuel conflicts in1920s China! If you leave aside skirmishes and small-scale clashes, between 1912 and 1930, China has on average 8 full-scale wars per year. Eight! Only 1914 and 1915 were free of conflict. 1928 was the all-time high with no less than 16 separate wars.

Numbers, numbers…

There is no accurate central record of the number of soldiers in this time. Those publicly stated by the Ministry of War in Beijing or others are, at best, dubious as numbers tended to be inflated to impress enemies. Diana Lary deems it safe to say that, between 1911 and 1928, soldiers quadrupled in numbers. Rough estimates have been made by scholars. Here below an estimation provided by Jerome Ch’en:

- 1919 – 1,400,000

- 1923 – 1,620,500

- 1923-24 – 1,500,000

- 1925 – 1,450,000

We would add to this Qi Xisheng’s estimation for 1928: over 2,000,000 soldiers in China.

Such numbers, for a country in peace time, are enormous. Guess what? Numbers presented above are only estimates of soldiers regularly enlisted in large armies! China’s armed men tended to be grouped together in common speech as bingtuanfei, soldiers-militiamen-bandits, whose “hierarchy” could be established as follow according to Diana Lary:

- Major armies (multi-province warlord, Guomindang),

- Local armies (single-province or multi-county armies),

- Petty armies (single county army),

- Militias (local defence forces at county-level, including merchant-raised ones),

- Bandits and pirates gangs,

- Irregular units (temporary forces made of bandits or secret society members),

- Mass units (masses of armed peasants, sometimes secret society members, sometimes political activists),

- Stragglers (individual soldiers detached from their unit),

- Local bullies (village enforcers).

That 2,000,000 soldiers 1928 estimation would only cover for major and local armies.

A clash of worlds: militaries-civilians

Before diving into the reality of being a soldier in 1920s China, there is a whole aspect to be considered first: relations with the civilian world. As soldiers do not exist outside of the society, interactions with the civilians cannot be overlooked. And, in China, these were more often than not negative and brutal.

Soldiers: unfit for a civilised Chinese society

« Don’t waste good iron for nails or good men for soldiers. »

Chinese proverb

« It is better to have no son than one who is a soldier. »

Chinese proverb

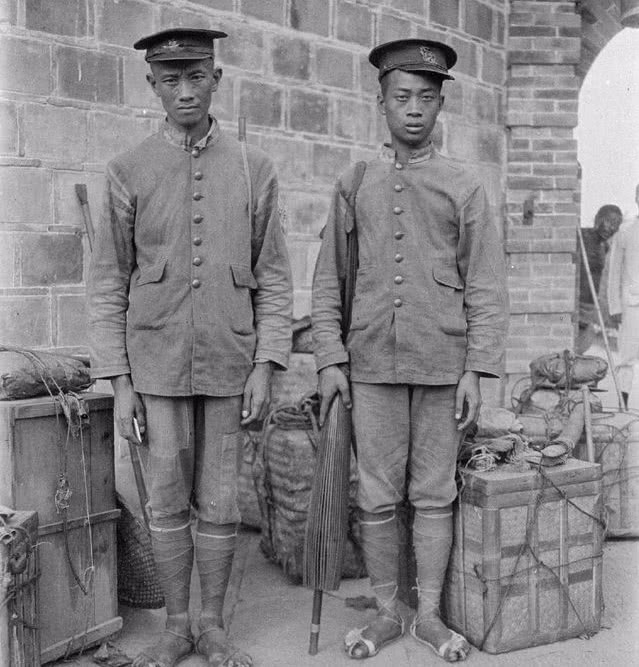

These two Chinese proverbs set the scenes. Being a soldier was associated with a lot of negative characteristics in traditional and warlord China. Though despised in the Chinese culture, the social status of soldiers started to evolve from the 1910s onward. This was however limited to high-ranking officers, whose status went up because the military had become the new route to power and wealth. Common soldiers, on the other hand, remained with a very low status

A man with a gun is dumb

Often considered stupid, uncivilised and rustic, soldiers were perceived by the Chinese civilians as “at best an unfortunate necessity and at worst as a painful burden”. Their alledged stupidity was mocked but it was also feared, considered dangerous. A dumb soldier would be malleable enough to do what his commander wanted (often to the detriment of the civilians). Wu Peifu’s troops fighting at Shanhaiguan in 1924 were reported to be “good fighting men” because of their “lack of intelligence” that had « annihilated » their sense of self-preservation. Stupidity was also correlated to an evil mental deficiency and / or deliberate sadism, consubstantial to soldiering. Civilians saw themselves as extremely superior to soldiers, mere creatures of abysmal moral standards.

Enlistment was seen as the acknowledgement of one’s unfitness for civilian society. In fact, the Chinese gave credit to the theory that some men were born soldiers, not made such. Only the rebel, violent and antisocial was thought to ever want to go to the army. Because of the bad character attached to soldiers, civilians were expected bad behaviour from them. Anybody wearing a uniform and having a gun was expected to be brutal, arrogant, stupid, cheating and thieving. These assumptions explain why civilians so much disregarded soldiers, whether the men in the uniform were actually bad or not.

Interestingly enough, officers often shared civilians’ assumptions about their own men. Both the Guomindang and Feng Yuxiang have been known for issuing lists of prohibitions based on what they saw as expectable soldier behaviour. These targeted the usual suspects: drinking, smoking, consorting with prostitutes, gambling or committing illegal acts. Some more specific regulations would be introduced like being forbidden to go behind the counter when negotiating with merchants. GMD soldiers were ordered in 1926 not to seize coolies, loot, steal provisions or requisition houses.

Where expectations meet reality…

The worst in all of this is that what civilians believed and expected about soldiers was rather true. Soldiers were more likely to be rustic, arrogant, brutal and greedy than fine young men of the highest moral standards. Soldiers of the Red Army were quite a (positive) shock in newly liberated areas, at least at first. But why would soldiers behave this way? Several explanations have been put forward:

- Soldiers behaved the way society expected them too: according to this explanation, the Chinese culture being averse to soldiers had the negative side effect of generating men who would prey on it as a revenge. We let you imagine the vicious circle: the worse the soldiers behaved, the more society hated them. This however fails to explain why « decent » people would end up as bullies, just like the more sadistic ones who came for power.

- Soldiers were rebellious teenagers: this one is a bit tenuous as it would equate that all soldiers were teenagers. If teenagers made quite a large part of armies, they were not the one and only source of soldiers. Moreover, rural society in China meant that teenagers never really had the luxury of being rebellious (because rebelling to one’s lot would probably mean death).

- Soldiers learnt their ways with the army: this is one explanation which covers the majority of soldiers and probably is the most convincing one. The army was breeding a mentality of brutality in soldiers’ mind. Being treated violently by their officers, soldiers replicated this behaviour toward civilians, knowing there would be little to no consequences. The lack of formal standards in the army, resulting from a military world in great upheavals after the Qing collapsed, made soldiers learn how to behave as they went along. However, it suited the army to have bad-behaved soldiers – who could terrify local populations into compliance.

Some attempts were made to bring up soldiers to a higher level of moral standards. Warlords like Feng Yuxiang, Li Zongren or Cai Tingkai. Their troops were commonly acknowledged as being of good quality, thanks to their more humane treatment of men. Most warlords did not bother: the effort would have been to great for insufficient rewards in a system such as warlordism.

Violences against the civilians

Violence was however unevenly distributed in China. Areas of regular military operations were more prone to looting then places garrisoned with well-disciplined troops. Soldiers were more dangerous in groups, taking strength in numbers, than alone. What was a constant anxiety for civilians was the unpredictability of violence, generating a constantly tensed and insecure situation. The rich could try and hide their riches behind bars or foreigners’ nominal possession (cases reported in Guangzhou in 1924). A luxuryt the poors had not. This made them the primary victims of army depredation.

Violence soldiers inflicted on civilians can be distinguished into two categories: by the army as an institution and by soldiers as groups or individuals.

Institutional violence

As an army, the following acts of violence against civilians can be identified:

- requisitioning of goods and special taxes: Peasants and urban masses took the brunt of these depredations, often carried out with the complicity of local elites and authorities. Things usually went this way : an amount of goods / money or services to be provided was stated by the military. The local elite / authorities were tasked to provide this amount. The officers did not care if more was privately embezzled along the process, as long as they got what they asked for.

- forced conscription of coolies: poor and ignorant men were the favourite target for conscription of coolies. They were sufficiently strong to be of use but stupid or not rich enough to buy themselves out.

- destruction of property (either through occupation or fighting): temples, schools and government offices were the most likely to be requisitioned and degraded by the occupying army. Fighting near civilian buildings also had quite a tendency to damage them, obviously.

- disruption of civilian trade and transportation system: places riddled with soldiers were avoided by traders and merchants (who, understandably, were not very keen on putting their wares at risk of requisitioning). Transportation system, mostly train, was regularly subject to requisition for troop transportation, free of charge. Again, areas of regular or intense fighting inevitably generated major disruption in trade and transportation.

Individual or group violence

Individuals soldiers or group of them would be associated with the following depredations:

- Looting: a different way of stealing, different from the legalised theft of requisitioning, which mainly fell upon urban residents though villages were sometimes a target. The risks of looting were especially high when a defeated army evacuated a city and/or a victorious army entered a captured city. Soldiers would go after material goods but anyone, rich or poor, who would stand in their way, was at risk to be killed. Some places like Chengdu, Xuzhou, Luoyang and Kaifeng were among the most looted towns in China.

- Rape: especially feared in a conservative society, women were preyed by soldiers on the loose. Though the fear of it was often more pervasive than the actual occurrences, rape still was a reality. Victims were considered soiled and their families would be dishonoured. It pushed women to stay in the care of their male relatives as much as possible.

- Theft: coming in two flavours. First, the actual direct theft where a soldier would take goods, money or services from a civilian (and, if an animal was on the vicinity, it would be taken as well to carry the product of the soldiers’ misdeeds). The second form was forcing payment in worthless paper or metal currency – like those printed by a warlord. The merchant would be forced to take them at face value rather than its actual one. You could add to this the practice of forced discount “negotiated” by the army and the merchants as well as barter for unwanted goods. One last type of theft was the practice of ransoming stolen goods to their previous owner. The poor was way more likely to be victims of theft, as the rich, whose possessions were behind walls and only accessible during times of looting.

- Vandalism and casual violence: regular manifestations of blind, purposeless violence were coming with an army. Occupied places would often be wrecked. For instance, the Gongyue Xuetang of Guangzhou was reduced to rubbles by Long Jiguang’s Guangxi troops during the three months they occupied the city. Smashing people for random reasons were also common. The direct purpose of this was to humiliate and degrade civilians.

Fighting back

Though military violence was endemic and apprently endless, this does not mean civilians never fought back. Militias and elites were nearly useless in fighting back as they preferred to find an arrangement. The people would sometimes take things in hand. In 1920, for instance, the people of Hengxian in Guangxi savagely attacked Cantonese stragglers who were retreating to Canton; the villagers murdered as much as they could. Even more surprising, the peasants of Shangzhi (Hunan) formed their own army in 1919 to resist forced labour. They remained in operation until 1929 and a crackdown by He Long. Secret societies sometimes organised resistance against marauding soldiers. In 1929, for instance, members of secret societies were reported to undertake actions against soldiers in Shaanxi and Shanxi.

We will conclude this long first part here for today. Hope you enjoyed this bit! Next time we will talk about the soldier himself, from recruitment to leaving the army. Stay tuned for more DDs and content!