Dear readers, fellow gamers,

We hope you are all well and rested. The time has come to talk once more about soldiers. Last time, we touched the issue of recruitment; from sources of men to the type of relations established between officers and their men. Let us resume our journey with Chinese soldiers and explore their life in the army!

Life in the army

Once enlisted, the new recruits had to be transformed into proper soldiers, acculturating to military culture and discipline. Common men first (and most often definitive) contact with discipline was the non-commissioned officer. A man who was tasked to break them and bend them to fit in the army.

Learning discipline the hard way

Let us be clear from start, China had no clear intermediary corps (NCO) between officers and men. The training sergeants were often long-service, experienced soldiers. Very few armies gave them proper NCO training. Actually, in quite a number of places, the NCO would only be differentiated from the rank-and-file by his seniority.

This acculturation and teaching of discipline was however never as harsh as in the German and Japanese armies. The reason behind this is the fact that recruits were mercenaries and expected some form of minimally decent treatment. Unhappy men had a very easy time deserting, leaving the warlord with those who wanted to stay or could not afford to leave. This does not mean that acculturation to military life was not hard. Poor clothing quality, awful food, constant drilling exercise, absence of medical care, violence from senior soldiers and officers, etc. were a daily reality.

Instrumental in the recruit assimilation into military life were the senior soldiers ‘Older brothers’ (老兄弟 Lǎo xiōngdì). They were usually running the barracks and were to one to be pleased. Pressure to fit in and adopt the army as a surrogate family was strong. The feeling of comradeship was also supplemented with the power coming from having guns.

Training

Training was often quite basic and oriented toward drilling exercises. Why is that? Simply because many armies could not afford to give men weapon training. This is why drilling was often the core training. Wu Peifu was known for the emphasis he placed on theses exercises. He expected his soldiers to excel at parading, presenting arms, standing at attention and goose-stepping. Others did their best to train men to fight. Li Zongren often boasted about the military capability of his men while acknowledging their sloppy outlook and manners.

Physical training often went along some form of indoctrination, which is different from the political training given to the GMD armies or in the Red Army. A good example is Feng Yuxiang’s indoctrination techniques leaning toward Christianity, mixing ‘catechisms and Socratic dialogues to inspirational song and hymns’.

Military fashion

The growth of a military officer cast came with a fascinating interest in military fashion. And this at a time where major armies elsewhere in the world were turning to more sober and khaki-ish uniforms. Officers sought to distinguish themselves from the mass of enlisted men wearing their low-quality greyish uniform. Western uniforms of the flamboyant kind, with gold medals and trimming everywhere, feathers on the hat, were praised by warlords. Lesser officers also loved adornments on their own uniform. In 1927, the north-western units used to describe their officers as ‘three golds and five leathers’ (Sān jīn wǔ pí, 三金五皮): gold-rimmed glasses, gold rings and gold watches; leather belt, pouches, boots, batons and gloves. No all officers had this love for exaggerated fashion. Feng Yuxiang, again, was more often seen in farm-boy outfit or field uniform though he kept his marshal-like one in the wardrobe. Couple of different styles shown here below:

CAO Kun (President of China, Zhili)

YUAN Shikai (President / Emperor of China)

FENGYuxiang (Zhili then Guominjun)

CHEN Jiongming (Guangdong)

TANG Jiyao (Sichuan)

ZHANG Zuolin (Fengtian)

Maltreatment and neglect

Even if a soldier’s living standards were probably better than a labourer’s, he would face maltreatment and neglect on a daily basis.

The army was not under civilian law and officers had full latitude with regards to abusing or punishing their men. A commonly accepted view was that treating men roughly would toughen them up for fighting.

The only disciplined soldiers were thought to understand was beating and lashing. Even if sanctions were ordered by officers, fellow soldiers were often made accomplices to physical abuse – sometimes partaking joyfully… Exemplary punishments, to discourage others, were common. Some commanders, like Feng Yuxiang (again!), did realise that beatings may secure temporary obedience but were in the end counterproductive. He issued in 1913 a set of guidelines. These listed instances in which officers were forbidden to beat their men (while letting a boatload of other cases were beatings were authorised). Officers complained at first, denouncing these as leniency that would only make soldiers disobedient and unmannered. They eventually stopped when desertion rate started to decrease.

Soldiers would also suffer from passive physical abuse, in the form of neglect of their welfare. They would often be crammed in dirty, overcrowded and bug-infested barracks, commandeered temples and schools; or tents, while in campaign. Lack of sanitation was the cause of standard infections and ailments in the camps. Scabies, eye and stomach infections, boils, ringworm, eczema, yellow / trench / relapsing and sand-fly fevers were common. Disease was actually a greater danger to soldiers than battles. Reports from Hunan (1938-1941) highlight that a soldier was six times more likely to fall ill than to be wounded. Some armies tried to take into account their men’s health. The Guomindang armies had instructions for the number, construction and location of latrines per men during their Northern Expedition. Feng Yuxiang ordered his men to clean their barracks, wash themselves and use latrines.

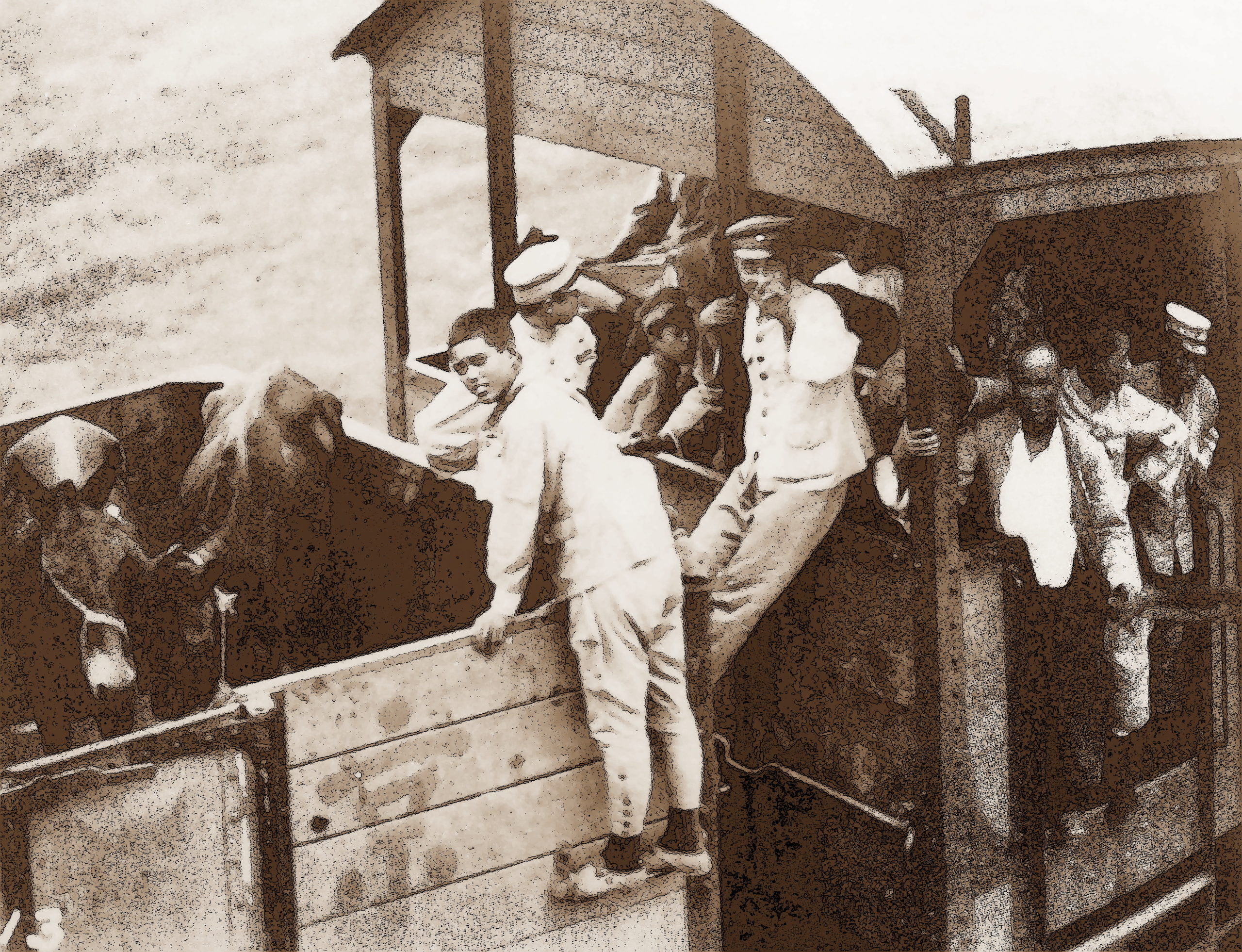

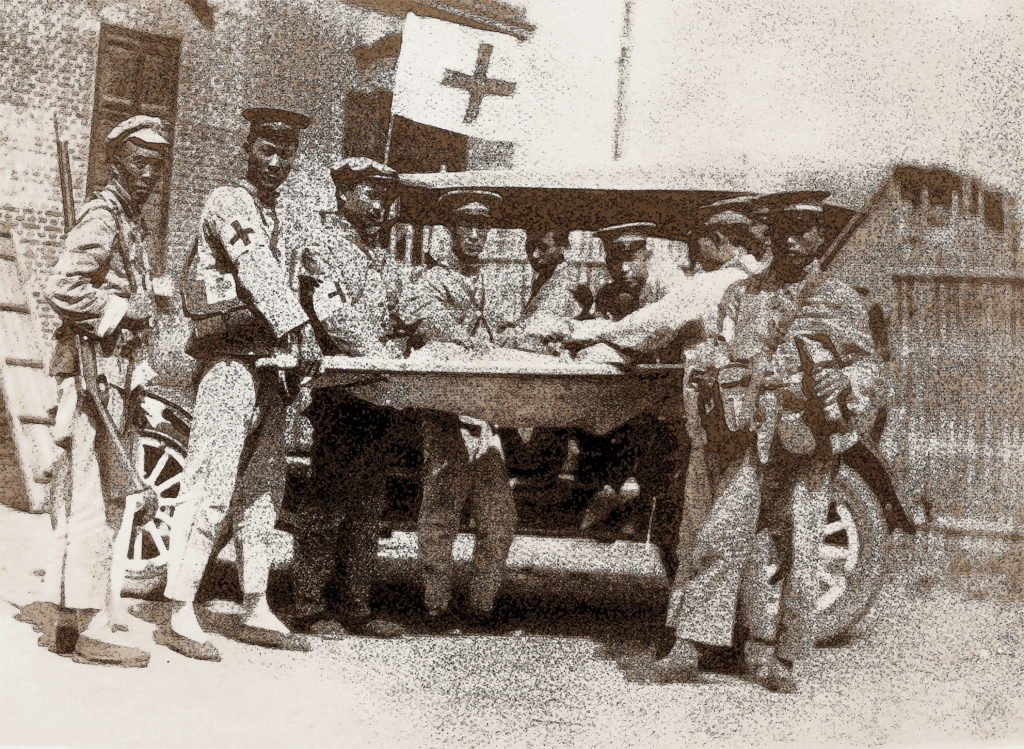

Should the soldier avoid falling ill, he would then face the danger he was supposedly paid for: the battlefield. Medical care was virtually non-existent as this was considered useless expenditure by warlords. Some instances of collaboration with mission hospitals happened but were rather rare. The National Revolutionary Army and Wu Peifu’s were among the rare armies to have a rudimentary medical branch. Being wounded would often equate to a lonely death as the injured soldier would be abandoned with no money.

Behaviour and entertainment

Most Chinese armies of the era saw discipline being rather respected while on duty. Surprising, eh? Well, just note that it was absolutely disregarded when being off duty. The few armies, like Feng Yuxiang’s, who upkept discipline even off-duty were known as the notable exceptions.

The Four Vices of the Soldier

In fact, the army condoned many off duty activities regarded as ‘despicable’ (gambling, drinking, prostitution, opium-smoking, etc.). It even provided its men enough free time to indulge in these vices. Whether a soldier paid or not for his pleasures was entirely up to his conscience. Some organisations like city authorities also took on themselves to offer soldiers with distraction like theatre plays to keep them off the street. Officers themselves sometimes even provided entertainment to their men to keep control over them and get back part of their wages. Let us take a closer look at these ‘activities’:

- Opium smoking in the army was mirroring the civilian consumption. The Yunnanese armies were notorious for being entirely comprised of addicts. Soldiers coming from provinces with high opium culture and caravan routes were also significantly more addict than armies from other regions, where consumption was more tied to specific unit.

- Prostitution was an important industry, considered sordid but unavoidable by the Chinese society. Some armies had camp followers but most relied on local ‘resources’. Though despised, prostitutes were however discreetly welcomed as they diverted the attention of soldiers from respectable women. Unfortunately, rape was not prevented by prostitution…

- Gambling was surprisingly a more regionalised form of entertainment. The Cantonese soldiers were recognised as the greatest gamblers, taking their provincial passion with them through their campaigns.

- Drinking was also a pastime but in lesser quantity and regularity than in other armies like the British or Russians.

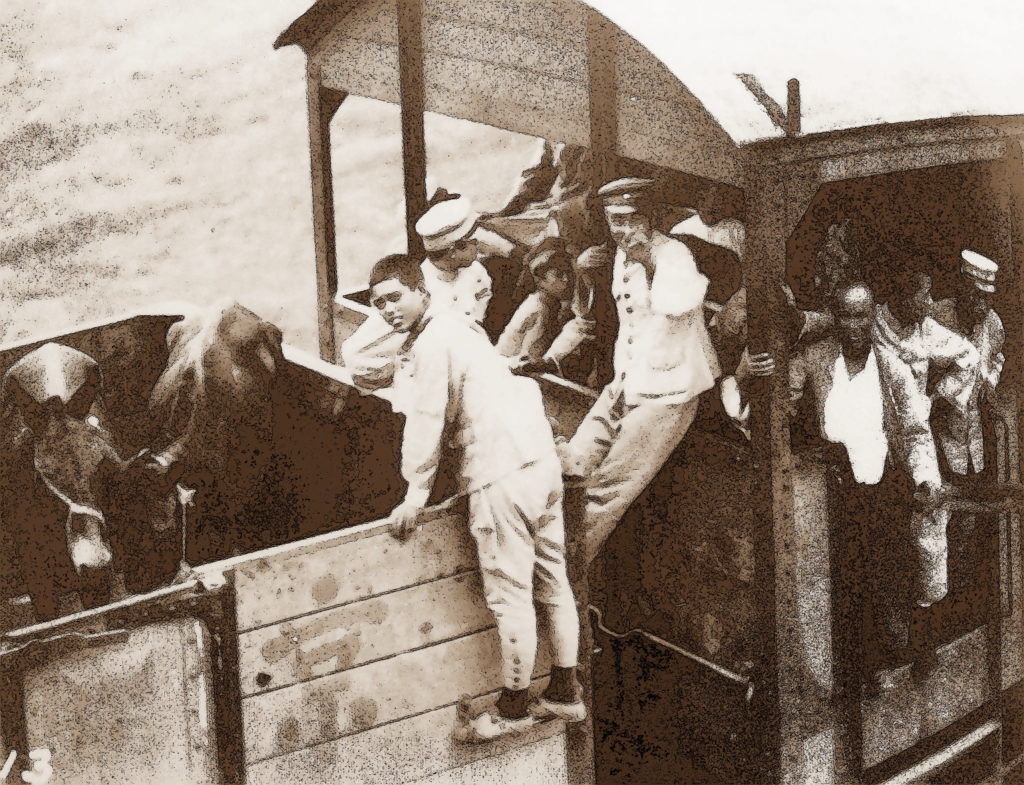

The Chinese tourist-soldier

Soldiers were often travelling on duty but also off-duty. Sight-seeing seems to have been quite a pastime. If walking was a common option, travel by boat or train was much appreciated. Soldiers travelled for free and took whatever seat they wanted. Neither sellers nor passenger would have wanted trouble with these armed men. The abuse of public transportation during soldier free time was also regular and often source of disturbances.

Actual prices for a soldier did not really matter at all given the fact that he was able to pay whatever he felt like, backed by his gun.

The purse and the stomach

What brought recruits to the army, besides the advantages of having a gun, was the pay. Formal wages existed and were supposedly known to the soldiers and prospective recruits. Here below is a table compiled by Diana Lary on monthly wages in different armies at different times:

| Sergeant | Corporal | First Class Private | 2nd Class Private | |

| Beijing 1915 | — | 4.8 taels | 4.5 taels | 4.2 taels |

| Guangzhou 1926 | 16 yuan | 14 yuan | 10.5 yuan | 10 yuan |

| Guangxi 1926 | 12 yuan | — | 10 yuan | — |

| Taiyuan 1929 | 9 yuan | 8 yuan | 7 yuan | 6.3 yuan |

The value of these wages depended on whether these were paid in metal currency (preferred by soldiers, surprise!) or paper money. Some commanders, whether greedy or on tight budget, were tempted by the printing of their own paper money or debasing metal currency. A good example is Feng Yuxiang who, in 1927, left with only 500 silver dollars in his coffers, printed some CN$20,000,000 to pay his men! Though soldiers could impose payment in paper money to civilians, they always preferred the sound of coins. Arrears of pay were extremely common and the most important cause of mutiny. Between 1911 and 1922, some 26 out of 80 mutinies were caused by payment issues. It was up to the commander to finely juggle with money and the mood of his soldiers and only pay them just before they explode in mutiny. Should they fail, this was often of no serious consequence to them. Poor civilians would be the victims of angry soldiers.

Pay mattered most to men who had dependents relying on their remittances. Family of garrisoned soldiers would be rather secure, having regular remittance and being able to cultivate rent-free military lend. The story was a lot different for those families whose soldier relative was away. Remittances would then be highly irregular and there could be long period without any source of income. Some armies were known for caring a lot for soldiers’ families, Feng Yuxiang’s being the first. Payment were sent regularly through army channels and special arrangements were made for families in need. For instance, in 1920, Feng Yuxiang did give special leave and sum of money to soldiers originating of Hebei where a severe drought had struck.

Soldiers were often complementing their promised revenues with extra sources. Among them, the pre-battle bonuses were fairly common in armies led by greed rather than zeal. Soldiers also traded their civilian skills to others like sewing, writing or moonlighting. Last but not least, a man could get some serious money from the sale of his uniform and even more from the sale of his gun. Demand was high and a lot of people would pay for a weapon, working or broken, with or without ammunition.

If pay was extremely irregular, commanders always made sure their troops had food. They knew all too well what would happen if men were left starving. This mean that serving in the army was always safer than remaining a labourer, despite the harshness of military life and danger of wound and death; the latter would indeed be starving and unpaid.

‘Silver bullets’

The large number of men under arms in Warlord China led to a strong propension of army commanders and men to be vulnerable to “silver bullets”. Bribery had been a long-standing tactics in the Chinese military history. During the Republican era, especially prior to 1922, bribing enemy army / unit commanders to have them withdraw from the battlefield or simply not shoot was common practice. One or two units bribed into refusing to join the fight were often enough to cause panic in enemy ranks. The GMD was not shying away of such tactics. During the Northern Expedition, as he was approaching Hankou with his army, Chiang Kai-shek bribed the garrison commander to surrender and paid CN$10 to each man to make sure none would resist. When reaching the nearby Wuchang, the deal proposed by Chiang to the garrison was that every soldier not resisting would be taken in in the National Revolutionary Army.

And this concludes part 3 of our series on Chinese soldiers in the 1920s. Stay strong, we are reaching the end of it! The next and final focus on this topic will be about leaving the army. In the meantime, we wish you all a good day!

Stay tuned for more DDs!

Le Visiteur